|

Private Douglas Cater: Regiment Musician

by

Rebecca

Blackwell Drake

Private Douglas Cater, 3rd Texas

Cavalry and later the 19th Louisiana Infantry, began his odyssey

with the Confederate Army on June 8, 1861. Like others fighting

for the Confederacy, the musician turned soldier was full of hope

that he could help to save his beloved Southland. "I told my

family and loved ones that we must be cheerful," he

reminisced, "having faith that I would return to tell them of

my varied experiences in the army." Cater was not the only

one in his family to say goodbye. Also marching off to war were

his brothers Wade and Rufus. Private Douglas Cater, 3rd Texas

Cavalry and later the 19th Louisiana Infantry, began his odyssey

with the Confederate Army on June 8, 1861. Like others fighting

for the Confederacy, the musician turned soldier was full of hope

that he could help to save his beloved Southland. "I told my

family and loved ones that we must be cheerful," he

reminisced, "having faith that I would return to tell them of

my varied experiences in the army." Cater was not the only

one in his family to say goodbye. Also marching off to war were

his brothers Wade and Rufus.

Private Cater traveled

with a bugle and a violin. "Col. Armstrong and I would take

our violins out of the baggage wagon at night when favorable

opportunity offered, and we would entertain the 'boys' with

music," wrote Cater. "We frequently played cotillions and

reels for them to dance. They would form a 'full set' by tying a

handkerchief around the left arm of those who were to act as

ladies as partners. Often there would be a hundred or more men

present to listen to the music, as well as to 'look on' at the

dance."

Cater's love of music and

his talents for entertaining helped the troops through many a hard

time, especially during the freezing winter of 1862 and the Battle

of Pea Ridge, where so many of his fellow soldiers were killed.

In the spring of 1863,

Cater and Rufus, fighting with the 19th Louisiana Regiment, were

ordered to Mississippi to help defend Vicksburg. "General

Bragg commanded that part of the army," Cater recalled,

"and was needing every available man to face the Federal

army, but Gen. Pemberton, who had disobeyed the orders of Gen.

Johnston to leave Vicksburg and come to him and was sustained in

this disobedience by President Davis, was needing reinforcements

at Vicksburg against the advance of General Grant." By the

time Cater arrived in Jackson on May 31st, Vicksburg was under

siege.

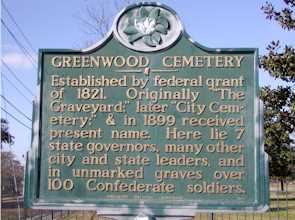

During their first days

in Jackson, Cater and Rufus, went to the city graveyard looking

for their lost brother, Wade. "After a long search in the

cemetery at this place [Jackson], found the grave of our beloved

brother Wade, which was marked by a plain board with his name and

the number of his regiment," wrote Cater. " He had

contracted cold in the trenches [Vicksburg] and was sent out to

Jackson where he died. We found a marble slab in an old marble

yard and cut his name, age and regiment on it and placed it at the

head of his grave."

|

Wade Cater fell

ill during the Siege of Vicksburg and later died in the

Confederate hospital in Jackson. He was buried in the

Graveyard with only a hand scribbled marble slab as a

marker.

|

After the fall of Vicksburg,

the 19th Louisiana was assigned to the trenches around Jackson. It

was here Cater managed to haul a beautiful old piano out of a home

destined to be burned. The piano was placed in the trenches where

Cater and Rufus entertained the troops playing and singing. At one

point, the men were so engrossed in their music making they forgot

about the enemy until the Yankees stormed the trenches. The men

ceased their music-making just long enough to defend themselves

against the approaching enemy - killing one hundred and sixty blue

coats.

After the fall of

Vicksburg, Cater and Rufus continued on to Georgia. During the

battle of Chickamauga, Rufus was killed. Recalling the sadness of

his brother's death, Cater wrote: "His blanket which he had

folded in the morning and carried over his shoulder, the ends tied

with a string at his side, had been unfolded and he was lying on

it, cold in death. His watch, his purse, the shoes from his feet,

his sword and scabbard had all been taken. His pants pockets were

turned wrong side out and the devils in human form not yet

satisfied, had fired a rifle ball through his forehead. The ball

through his forehead was sufficient evidence that he was murdered

while a prisoner on the battlefield."

With two brothers lost to

the Confederate cause, Private Cater still continued with his war

efforts. Adding to his sadness was a letter from home informing

him that his nine-year old brother had also died. All too well,

the music-making soldier had come to know the pain of death.

Private Cater continued

fighting through the Siege of Atlanta and the Battle of Franklin,

also known as one of the worst 'blood baths' of the war. Recalling

the poor leadership by General John Bell Hood in the Battle of

Franklin, Cater wrote a stinging review: "We are now going to

witness a manifestation of General John B. Hood's great

generalship. Does he order his whole army forward? Oh, no! There

is a little field in front of the enemy's breastworks large enough

for a little division to form a line across it. The army is

halted; a division is sent across the field to take the enemy's

breastworks. It fails and must retreat across that field under

fire, the same as when facing the enemy. A second division makes

the same effort and meets the same results. A third division, and

another were sent, both with the same results. Gen. Cleburne and

his staff and all their horses are left on the breastworks. Our

division is to make the next assault, but darkness has come and we

must wait till the next morning. When the morning came we started.

We must be careful least we step on a dead or wounded soldier. We

went across the same field to the breastworks. We met no

opposition. The enemy had gone to Nashville. We found the trenches

filled - not half-filled - but filled with dead men, both Federals

and Confederates."

The Battle of Franklin

sounded a death knoll for the Confederate Army. Private Cater and

the 19th Louisiana Infantry retreated, saving what they could of

their army. There was no victory and each and every one of the men

had paid a terrible price..

Seven months after the

Battle of Franklin, Cater was mustered out of service and returned

to the family home in Louisiana. Of the homecoming he wrote:

"I cannot tell of my own feelings as I dismounted at the gate

and heard the faithful watch dog's bay deep mouth welcome. I knew

welcome awaited me, not as a returning prodigal, but as the only

one left of the three this home had furnished as soldiers to the

Confederate States army."

Some time later, Cater

recalled his promise to tell his family of his war experiences.

Using an Indian Head tablet and a pencil he began writing his

memories: "Three years? Yes, it is just three years today

since I bid adieu to Texas friends and took up the line of march,

a soldier of the Confederate States….."

Historic Source: As

It Was: Reminiscences of a Soldier of the Third Texas Cavalry and

The Nineteenth Louisiana Infantry by Douglas John Cater. Pvt.

Cater's diary and memoirs were collected by William D. Cater,

grandson, and first published in 1981. The book has recently been

published [1990] by State House Press, P.O. Box 15247, Austin,

Texas, 78761.

|