|

Seventh Texas Infantry: by Rebecca Blackwell Drake

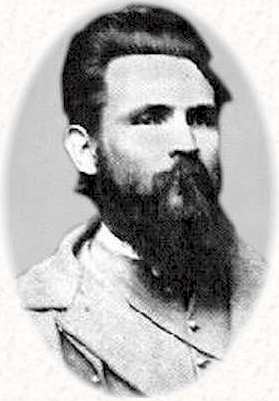

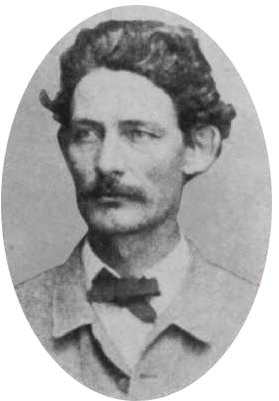

In 1858 in Morgan County, Alabama, John Gregg and his bride, Mary Francis Garth, stood before a magistrate and repeated their vows, "In sickness and in health - Till death do us part." Following their marriage, the couple left for Fairfield, Texas, where Gregg served as District Judge. He also founded the first newspaper in the county, the Freestone Country Reporter. In that same year, March 31, 1858, Hiram B. Granbury, a former Mississippian who had moved to Waco in the early 1850s, stood with his 20-year old bride, Fannie Sims, formerly from Alabama, and repeated the same vows. Hiram Granbury served as the chief justice of McLennan County, Texas. During the early years, he had helped to establish the newspaper in Waco. In 1861, after Texas seceded from the Union, John Gregg organized the 7th Texas Infantry, a group of 746 men recruited from nine East Texas counties. That same year, Hiram Granbury formed the Waco Guards that would soon become a part of the 7th Regiment Texas Infantry. In the fall of 1861, both men, still in the honeymoon years of their marriage, left Texas to fight in the war. In February of 1862, the 7th Texas and other Confederate regiments were captured at Fort Donelson, Tennessee, and John Gregg and Hiram Granbury were taken prisoner. Stunned over the turn of events, Granbury and a friend, Capt. K. M Van Zandt, decided to approach General U. S. Grant to make several requests. First, they requested that Colonel Clough (killed in action) be given a proper burial. Secondly, they requested that Col. Granbury be given some time before being taken prisoner in order to settle his wife, Fannie. During the early months in Hopkinsville, Fannie had been the houseguests of the Steven Trice family, supporters of the Confederate cause. However, in 1862, when the epidemic of measles began to spread throughout the camp, Fannie moved to Clarksville, Tennessee, a distance of some twenty-five miles. General Grant listened to Granbury and Van Zandt's petition and surprised everyone by granting both requests. As Granbury traveled to Clarksville to make plans for Fannie, Mary Gregg paid for a train ticket and took the train to Decatur, Alabama. At first Granbury and Gregg were imprisoned at Fort Chase in Columbus, Ohio. However, on March 6, 1862, they were moved to Fort Warren Prison in the Boston Harbor. Fannie rode the train from Columbus, Ohio to Boston, Mass. with the soldiers. However, after arriving at the Boston train station, she was not allowed to accompany the prisoners out to Fort Warren, an island six miles from Boston. Thanks to the kindness of Granbury's cellmate, Dr. Charles McGill, a physician, Fannie was taken in as a house guest of Mary McGill in Hagerstown, Mass. During her stay with the wife of Dr. McGill, Fannie began to experience problems with abdominal swelling. In July of 1862, she made an appointment to meet with a physician in Baltimore for exploratory surgery. Granbury was released from prison [prisoner exchange] in order to attend the surgery. A letter to Col. J. Dimick, U. S. Army, Fort Warren, Boston, documents Granbury's early release: "Washington, July 29, 1862. The eight or nine prisoners referred to and those who have taken the oath of allegiance will not be sent to Fort Monroe; Parole Major Granbury, of Texas, that he may attend his wife having a surgical operation performed at Baltimore, then to report to General Wool, in Baltimore. L. Thomas, Adjutant-General." The outcome of the doctor's appointment was never made known. However, after examining Fannie, Dr. Smith apparently made the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The prognosis was only months to live. Fannie and Hiram decided to get a second opinion and went to Richmond, Virginia. Again, the reports of the doctor were not publicized but it was obvious by this time that Fannie and Hiram were in the throes of accepting a death sentence for Fannie. Since Fannie was no longer able to withstand the traveling that it took to keep up with her husband, Fannie returned to the McGill residence in Hagerstown where she would reside until Hiram could come for her. Following his release from prison, Granbury was promoted to the rank of colonel with the 7th Texas and sent to Texas on recruiting duty. General Gregg was also exchanged from prison and promoted to brigadier general August 29, 1862. At this time, he was given command of a brigade consisting of the Seventh Texas, Third Tennessee, Tenth Tennessee, Fifth Tennessee, and Forty-first Tennessee Infantry regiments and a battery of light artillery. In October of 1862, Granbury went to Hagerstown to get Fannie. Her health was declining rapidly and she wanted to be back in Alabama in the home of her father. On March 20, 1863, Fannie passed away in Mobile, eleven days before what would have been their 5th wedding anniversary. On March 21, her obituary appeared in the Mobile Advertiser and Register: "DIED on yesterday at 11:00 A.M., Mrs. Fannie Granbury, aged 25 years, Wife of Col. H. B. Granbury, 7th Regiment Texas Infantry. The funeral will take place from Providence Infirmary, at 3 o'clock P. M. TODAY." Unable to afford a headstone, Fannie was buried in Magnolia Cemetery, in an unmarked grave. Colonel Granbury and General Gregg continued fighting in the war. On May 12, 1863, less than three months after the death of Fannie, Gregg's Brigade was ordered to Raymond, Mississippi, to defend against the approaching Union Army. The battle was an overwhelming loss for the Confederates. Gregg's Brigade was forced to retreat. On September 19, 1863, Brig. Gen. John Gregg was severely wounded during the Battle of Chickamauga and was taken to a Confederate hospital in Marietta, Georgia. Once again, Mary Garth traveled to be by his side and to assist with his recovery. This was perhaps one of their last chances to be together in life. One year later, Oct. 7, 1864, while fighting in Virginia, Brig. Gen. John Gregg was killed. His marriage had lasted less than six years. Mary Garth heard the news of her husband's death while staying at her father's plantation in Alabama. "Her soul was plunged in grief beyond all other grief," friends recalled. After several months of grief and depression, Mary Garth decided she could not rest until she traveled to Virginia to claim her husband's body. Traveling with Sgt. E. L. Sykes, a Confederate soldier and family friends, Mary left on January 18, 1865, to reclaim her husband's body. They arrived in Virginia a month later but overwhelmed by the experience, Mary Garth succumbed to a nervous breakdown. They had to wait weeks before she could recover enough of her strength to make the long journey back. In April of 1865, Mary Garth Gregg finally arrived in Aberdeen, Mississippi, where she laid her husband to rest in the Odd Fellows Cemetery on the outskirts of town. Like Brig. Gen. John Gregg, a friend in love and war, Brig. Gen. Hiram Granbury, also went to his death a hero. He was killed Nov. 30, 1864, during the Battle of Franklin. Witnesses of the blood bath at Franklin reported, "General Granbury was hit in the eye about the same time Gen.Patrick Cleburne was hit in the chest. The bullet passed through his brain and exploded at the back of his head. He threw his hands up to his face and fell dead instantly." Granbury was initially buried near Franklin but later his body was reinterred at St. Luke's Cemetery, Ashwood, Tennessee. In 1893, his body was once again moved - this time to Granbury, Texas, a town named in his honor. A lonely, unmarked grave in Mobile and a faded obituary are all that remain of his beloved Fannie. Of the foursome in love and war, Mary Garth Gregg was the only one left. She remained in Aberdeen, Mississippi, where she could be near her husband's grave. For the remaining thirty years of her life she never left the town where her husband's remains were interred. When Mary Gregg died in 1897, she was buried next to her famous husband. Her tombstone reads, Mrs. General John Gregg. Sources: Force Without Fanfare, by K. M. Van Zandt and edited by Sandra L. Myres, published by Texas Christian University Press, 1995 (http://www.prs.tcu.edu/prs/); Letter from L. Thomas, Adjutant-General to Col. J. Dimick, U.S. Army, Fort Warren, Boston, dated July 29, 1862; Official Records of the Civil War; Compiled War Records from the State of Texas, Harold B. Simpson History Complex, Hillsboro, Texas; Cemetery Records of Mobile; March 21, 1863 Obituary of Fannie Granbury from the Mobile Advertiser and Register; An Account of the Burial of Gen. John Gregg in Mississippi, 1865, by E. L. Sykes, Aberdeen, Mississippi; Autograph Album of Col. John Towers, 8th Georgia Volunteer Infantry (prisoner at Ft. Warren); Lone Star Generals in Gray by Ralph Wooster; 1858 McLennan County Marriage Records, Intrepid Gray Warriors by James Newsom (PhD Dissertation from Texas Christian University on the 7th Texas Infantry). Assisting Rebecca Drake in researching this article were: Jane Ambrose, Ashland, Ohio, descendant of the Granbury family; Mary Eddies Johnson, professional genealogy researcher from Mobile; and Edward Lanham, Atlanta, Georgia, Civil War researcher.

Related

Links

|